I’m listening to the sounds of Paula, Ashley’s mom, moving about in the kitchen, opening cupboards, pouring coffee, setting the dog bowls on the floor. This morning we slept in till seven and while this is a real achievement after yesterday’s 5 AM wakeup, I can’t help feeling that I’ve lost some time, the darkness and peace that I need in the mornings. Now instead of feeling like I’m the only person alive, drifting in the timeless space before the day begins, I feel like I’m hiding in our bedroom. I want to get up to refill my cup of coffee, but I’m not ready to talk to anybody. I’m not ready to see anybody. I need to keep hiding just a little longer.

I absolutely love the book that I’m reading this morning, a novel by Rachel Joyce called The Music Shop. I’ve had so much luck lately choosing books solely by mood and intuition instead of enacting some vague plan: “I should read a classic” or “I should read one of the paperbacks I just bought at Half Price Books.” Have I mentioned that we went to a bookstore for the first time in six months? I’ll have to tell you about that later.

What I love about The Music Shop is the way the characters talk about music, about listening deeply. I’m talking particularly about Frank, the main character. He’s a the owner of an eclectic record shop in late-eighties England, a vinyl-only guy, one of the last hold-outs in a world that is being completely consumed by CDs, that shiny new digital format, clean, pristine, and perfect. Frank’s special talent is listening to his customers and diagnosing the precise music they need in their lives right now, whether they know it or not. For example, in the opening chapter, a sad pale man with a broken heart comes in asking about Chopin. “I only like Chopin,” he says. But Frank listens to him, looks him up and down, and puts him into a listening booth with a track by Aretha Franklin, “Oh No Not My Baby.” “No, this is what you need,” he says. And Frank is right, one hundred percent right. The music opens up the man’s heart and lets him feel some of what he’s been keeping bottled up. He finds self-expression by listening deeply to Aretha Franklin’s plaintive, passionate, soul-rousing song.

I’ve been wanting to listen to music like this myself. I mean, setting aside the time, shutting down all distractions, and just listening. Frank talks about this in the book. Everybody knows “Moonlight Sonata,” but no one ever listens to it. Not really. Music isn’t meant for the background. At one point, Frank tells Ilse, the woman he loves, that she has to lie down when she listens to the record he gives her. Lie down flat and put on a pair of headphones. Don’t do anything else. There comes a point where you can see the music. You can see the stories it has to tell you. Listening in this way can change your life.

When was the last time you really listened to music—without holding your phone or fixing a sandwich or driving to the grocery store?

We are six months into the pandemic, into this huge disruption of our lives. But there is still time to develop new routines like this, like lying flat and listening deeply. Routine isn’t even the right word, is it? Deep listening is so powerful that it can become a ritual, an essential practice, a prayer.

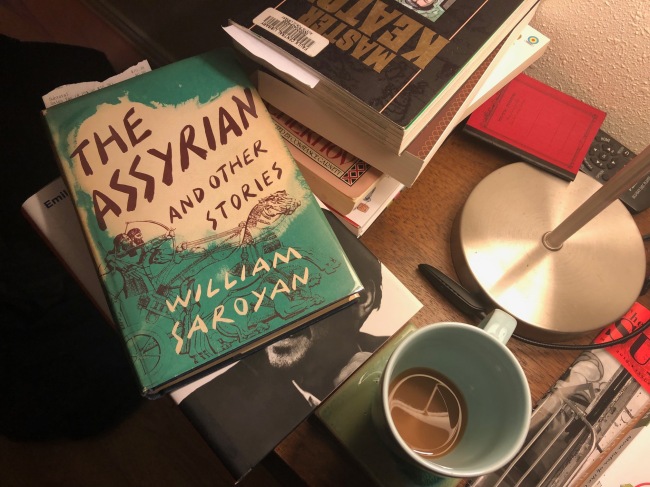

Monday night I switched off the TV, put on a Chet Baker record, and lay back on the sofa to read. Do you know what I picked up? William Saroyan. I’m sure he was on my mind because of our upcoming trip to San Francisco. All I know is that I felt drawn to his stories again. I found my copy of

Monday night I switched off the TV, put on a Chet Baker record, and lay back on the sofa to read. Do you know what I picked up? William Saroyan. I’m sure he was on my mind because of our upcoming trip to San Francisco. All I know is that I felt drawn to his stories again. I found my copy of